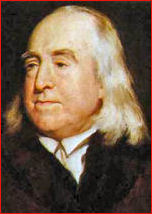

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832)

Jeremy Bentham |

The Panopticon |

But Bentham's most important and far-reaching invention was not any visible or tangible item. Nor was it a mere word. It was a philosophy, and one that has made a deep (and in my assessment, disastrous) impact on human history. Bentham was the inventor of utilitarianism, a way of thinking that begins with the assumption that "good" is defined by whatever produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Bentham's famous godson, John Stuart Mill, later refined and popularized utilitarianism as a philosophical system, but Bentham is the true father of the idea. (Perhaps godfather would be a more fitting term here.)

Bentham's philosophical outlook naturally set him at odds with eighteenth-century morality, which was largely inherited from the biblical and evangelical world-view of the Puritan era. His utilitarianism also made him a bitter critic of the entire British legal system. He argued, for example, that sodomy should be decriminalized. His treatise, "Offences Against One's Self," was not published in his lifetime, but it stands as a classic and very early example of how the utilitarian argument affects one's perspective on moral issues.

Bentham was born into a prosperous family of lawyers in the Spitalfields area of London. The family had apparently never been particularly devout Christians. (One of Bentham's great-uncles on his mother's side was a printer who published the first edition of Matthew Tindal's Deist manifesto Christianity as old as the Creation—arguing, like the Sadducees and the Socinians, for a naturalistic and moralistic religion devoid of any supernatural elements.)

Bentham's father realized Jeremy was a prodigy and pushed the young boy through college at an early age. The elder Bentham wanted his son to become a lawyer, but his heavy-handed fathering (combined with the fact that Jeremy went through his entire academic career as the youngest, smallest, most maladjusted student in every school he ever attended) made the young Bentham a reclusive, critical, social misfit with wonderful literary and academic skills. Those traits colored his whole life and philosophy.

Jeremy Bentham became a bitter and outspoken critic of the best-known legal expert of his time, William Blackstone. (Blackstone, of course, was one of the most pivotal and important figures in the history of British jurisprudence.) Although Bentham was essentially unemployed and unemployable as a lawyer himself, he loved the critic's role.

He was enabled to become a full-time critic when he inherited a small fortune upon the death of his overbearing father. Now independently wealthy, Jeremy Bentham made the most of his independence. He moved into a house in Westminster once occupied by poet John Milton. There he became something of a recluse and an eccentric. He named his teapot "Dickey," his walking-sticks "Dapple" and "Dobbin," and his cat "The Reverend Dr. John Langhorne."

Nonetheless, because his writings were filled with lucid prose and passionate arguments, he influenced the world. (I guess Bentham was, in a way, the original and quintessential superblogger.) He wrote for the next forty years, producing ten to twenty manuscript pages per day.

Bentham's legacy is still felt today in at least two major trends that have affected our world profoundly. First, he seems to have played a significant role in unleashing terrorism as a modern strategy for politics and revolution. His writings had a major impact on the Jacobins during the French Revolution. They justified the use of terror as a political tool with utilitarian arguments borrowed from Bentham. Bentham argued against natural rights, calling the concept "nonsense upon stilts." (A modern edition of his essays from that era was published a few years ago with the title Rights, Representation, and Reform: Nonsense upon Stilts and Other Writings on the French Revolution.) The arguments often given to justify terrorism today still owe much to the ethics of Bentham's utilitarianism.

Second, the moral and ethical relativism at the heart of most postmodern thought also finds its origin in Bentham's utilitarian system.

Obviously, Bentham was not someone whose thinking I admire.

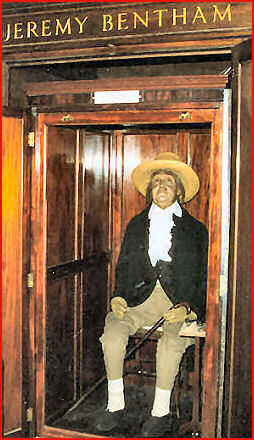

The Auto-Icon

The Auto-icon |

In his will, Bentham bequeathed much of his fortune to the University of London (now known as University College London). Along with the bequest, he had some very specific instructions about what was to be done with his remains. Bentham had actually planned for the disposition of his body for many years. As a matter of fact, the portion of his will that deals with the preparation and final interment of his remains is worth reading:

My body I give to my dear friend Doctor Southwood Smith to be disposed of in manner hereinafter mentioned. And I direct that as soon as it appears to anyone that my life is at an end, my executor (or any other person by whom on the opening of this paper the contents thereof shall have been observed) shall send an express with information of my decease to Doctor Southwood Smith requesting him to repair to the place where my body is lying. And after ascertaining by appropriate experiment that no life remains, it is my request that he will take my body under his charge and take the requisite and appropriate measures for the disposal and preservation of the several parts of my bodily frame in the manner expressed in the paper annexed to this will, and at the top of which I have written 'Auto-Icon.'

The skeleton he will cause to be put together in such manner as that the whole figure may be seated in a Chair usually occupied by me when living, in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought in the course of the time employed in writing. I direct that the body thus prepared shall be transferred to my executor He will cause the skeleton to be clad in one of the suits of black occasionally worn by me. The Body so clothed together with the chair and the staff in my later years borne by me he will take charge of And for containing the whole apparatus he will cause to be prepared an appropriate box or case and will cause to be engraved in conspicuous characters on a plate to be affixed thereon

His wishes were followed to the letter.

His wishes were followed to the letter.Unfortunately, Dr. Southwood Smith botched the embalming of the head. Bentham would no doubt have been deeply disappointed by this. He had personally selected the glass eyes that were meant to be used in his embalmed head, and carried them in his pocket for a decade before he died.

Let's allow the good doctor himself to describe what happened to the philosopher's head:

I endeavoured to preserve the head untouched, merely drawing away the fluids by placing it under an air pump over sulphuric acid. By this means the head was rendered as hard as the skulls of the New Zealanders; but all expression was of course gone.

Today the head is shriveled and macabre:

Doctor Smith continues:

Seeing this would not do for exhibition, I had a model made in wax by a distinguished French artist... The artist succeeded in producing one of the most admirable likenesses ever seen. I then had the skeleton stuffed out to fit Bentham's own clothes, and this wax likeness fitted to the trunk. This figure was placed seated in the chair on which he usually sat; and one hand holding the walking stick which was his constant companion when he was out, called by him Dapple. The whole was enclosed in a mahogany case with folding glass doors.

Nowadays, Bentham's actual head is reportedly kept in a vault in a storeroom not far from the corpse, which sits in a hallway at the University College London. But a familiar picture does exist of Bentham's dessicated sconce on display at his own feet.

Nowadays, Bentham's actual head is reportedly kept in a vault in a storeroom not far from the corpse, which sits in a hallway at the University College London. But a familiar picture does exist of Bentham's dessicated sconce on display at his own feet.A very informative article posted on the Web informs us that "The 'distinguished French artist' who made the wax replacement head was Jacques Talrich (d. 1851), a medical man who turned to anatomical modelling after military and general medical practice. His models in wax and in plastic materials found their way to museums in Britain, Germany, Russia and the United States, as well as in France, where he was modeller to the Paris School of Medicine."

British sensibilities being what they are, perhaps it is no wonder that the College has never done much to give deliberate publicity to the Auto-icon. In fact, at first, Dr. Southwood Smith retained possession of the corpse-case. He apparently kept it at his own home until about 1850, when it was finally moved to the College. Dr. Smith recorded, " When I removed from Finsbury Square I had no room large enough to hold the case. I therefore gave it to University college, where it now is. Any one may see it who enquires there for it, but no publicity is given to the fact that Bentham reposes there in some back room. The authorities seem to be afraid or ashamed to own their possession."

Perhaps privately, however, University Regents were not so embarrassed by the Auto-icon. Nor have they always relegated their famous philosopher-benefactor to an out-of-the-way closet. One legend has it that for many years, the cabinet with Bentham's corpse would be brought into Regents' meetings and placed at the head of the table. The minutes would solemnly state, "Jeremy Bentham present, not voting."

The legend is exaggerated, no doubt. According to one of the more credible sources, the fact of the matter is that "the auto-icon has attended very few meetings. The only such meeting of record was hosted by the Bentham Club on 24 February 1953 in the men’s staff Common Room. Otherwise, with the exception of the German exhibition planned for 2002, its appearances have been of the ceremonial sort."

Nonetheless, more than 150 years after Bentham's corpse was handed to the College, he's still there, on display, and not at Madame Tussaud's. They mustn't be too embarrassed by it.

11 comments:

Ummm, it's Sunday?!?! Getting a head start of the blog, are we?

It may be Sunday where YOU are. It's been Monday on the east coast for more than 2 hours already. I hafta go to bed, so I'm posting according to Mountain Time tonight.

very interesting... i used to study at UCL (which incidently is actually seperate to the hospital which still exists under the UC Hospital name), and wander past this macabre sight most days.

Are you trying to tell us something? Where might your head show up one day? Will this be part of the tour at GTY in the distant future? "Ladies and gentlemen, to your right is the head of the late editor/elder/blogger Phil Johnson." Thanks Phil for the disturbing images before I drift off to sleep.

It is now 7:15 AM EST and I am still scratching my head, which, as near as I can tell, is still attached.

Nonetheless, because his writings were filled with lucid prose and passionate arguments, he influenced the world. (I guess Bentham was, in a way, the original and quintessential superblogger.) He wrote for the next forty years, producing ten to twenty manuscript pages per day.

I have always been impressed to think that some of the greatest writers, such as Dickens, wrote their masterpieces in manuscript. I wonder how prolific current writers would be without spell check and all those other technological goodies.

Creepy pictures. Do you have a thing for dead bodies Phil?

Anyway by the time Monday comes round where you live it is nearly Tuesday here.

Great piece! James Crimmins notes the "dechristianization" intent (a "celebration of blasphemy") of Benthem's Auto-Icon: "Auto-Icon was intended to show the irrelevance of religion to the issue of the disposal of the dead. In this respect, Bentham’s approach was consistent with the emerging tendency of the age to demystify death, strip it of its Christian symbolism and ritualized terror, in favour of a focus on the material means of increasing human happiness on earth...In the idealized Utilitarian society there would be no God and the absurd idea of an immortal soul would be replaced by the posterity of the auto-icons." -- James Crimmins, "Jeremy Bentham's Auto-Icon and Related Writings"

"rendered as hard as the skulls

of the New Zealanders." There you go - New Zealanders are even better at head shrinking. Actually it was the local Maori who would shrink the heads of enemy chiefs. However, the demand created by European curiosity hunters and museums and the guns and tobacco fetched in return resulted in any lowely captive's head being elevated to chief status in shrunken form after the application of a suitable tattoo.

Looks like Bentham is trying to "save face" these days about his claims.

Campi

And I thought I was weird!

Phil, did you intend to maximize the international fame of this man who sought to de-codify the British legal system?

Post a Comment